What Happened To The Sweetness?

Jaffas have a long and beautiful history in Aotearoa. We’ve eaten them at movies, we’ve rolled them down hills, but how often have we stopped and asked why they are called Jaffas? Words by Lavi Small.

Jaffas have a long and beautiful history in Aotearoa, but they are also intimately linked to the history of Palestine, the land of the oranges who gave Jaffas their name. Before chocolates were coloured and flavoured with orange, another Jaffa existed; a bustling trade port, Palestine’s doorway to the world, a city painted with the scents of orange blossom and the salty sea that delivered oranges to the world.

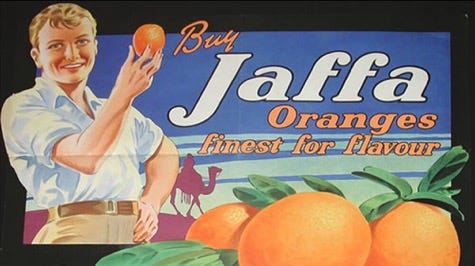

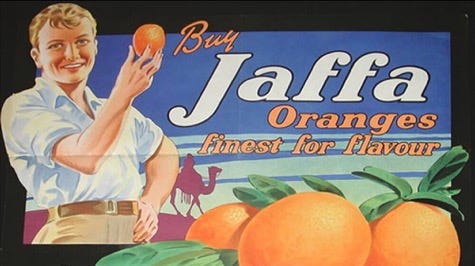

In 1931, when Jaffas first appeared for sale, oranges from Jaffa were wildly popular. Renowned for their thick skin, their sweetness and their lack of seeds, the shemouti or “Jaffa” oranges were one of Palestine’s biggest exports. They travelled well, they were easy to peel and most importantly they tasted incredible. The city of Jaffa was full of orange orchards, introduced in the 10th Century and growing the same variety of fruit since the mid-19th century when Ottoman Palestine first began trading them. Arabs owned orchards and Jews worked in them, Jews owned orchards and Arabs worked in them. The trees were rooted in soil that knew the feet of Jews and Arabs as equals. The world knew Palestine as “The Land of Oranges”, posters bearing pictures of glowing-golden fruit encouraged people to “Visit Palestine” and “Buy Jaffas”. Queen Victoria named them the citrus fruit at The Royal Table. In Jaffa camels laden with bright globes of fruit, carefully wrapped in their individual papers, walked from orchards to the sea. Between the World Wars, the orange industry boomed as the sun shone down as one giant orange in the sky.

For years the orange was a symbol of identity to Palestinians. To Indigenous Arabs and Jews they were a symbol of light and strength, a testament to the way they worked with not on the land. Orange trees were an extension of the self, bright and sweet and springing, strongly-rooted from the earth. To Jewish refugees who had fled Europe they were a symbol of hope. Jews and Arabs continued growing Oranges, side by side, with only healthy competition, at one point there were equal numbers of Jewish and Arab growers of the fruit that made up three quarters of the total fruit (excluding olive) production for export. In the early 1920s when Palestinians were asked to vote on a flag the responses overwhelmingly contained the colours orange and green.

In the 1930s as the Zionist population grew with the arrival of more Jewish refugees to British Mandated Palestine the competition began to change, Kibbutz were set up hiring exclusively jewish workers. Spain began producing more oranges with cheaper labour and lower shipping costs. Drought led to lower quality fruit and trade restrictions were implemented which hurt the Palestinian exports and the people whose lives relied on them. Then in 1947 a partition plan was created, separating Arab Palestine and Jewish Israel. Jaffa, of which Tel Aviv was once a small Jewish area, was set to be part of Palestine, not Israel.

But in April 1948 Jaffa was besieged and pounded by what would soon be known as the Israeli Army. Land was destroyed, once fertile orchards were left twisted and smouldering. Palestinians fled, crammed into boats with none of the care with which their fruit had once been packed. No care for bruises or scars. No papers. Only desperation to escape the violence. Their roots left twisted and torn. On May the 14th 1948 the State of Israel was declared, and Jaffa became known as Tel Aviv-Yafo. Of the more than 70,000 Palestinians who had once lived there only 4000 remained.

But the Jaffa orange was still famous, a symbol of prosperity to the Israelis in their new found homeland. A symbol of hope for freedom and connection to their ancestral homeland for the Palestinians. Fruit that still bore the name Jaffa proudly on its label a symbol of all that was lost. Zionist agencies took over, absentee laws were created meaning that property could be seized if no one was home. These laws were distorted, orchardists went to work amongst the trees and returned to their houses to find someone else at “home”. With nowhere to live these people were forced to leave, carried out to sea on rivers made of their own salty tears.

But the Jaffa orange was still famous. The world knew them, they brought in money. Orange growers of Arab Jaffa and Jewish Tel Aviv signed a non-aggression agreement to protect the orange orchards. They would not be attacked, harvests and exports would continue. But the militia disagreed and random attacks continued to destroy them.

Zionist agencies and new Jewish settlers claimed the orchards for themselves, but they had none of the generations worth of knowledge of working with the land. They attempted to work on it, demand from sad trees who’d felt the violence too. The oranges still grew, now labelled “Jaffa Orange, Israel”, and their sweetness drowned in memories of bitterness. New orchards were planted, Zionists claimed they had modernised the cultivation of fruit, and these “modern approaches” became a symbol of an Independent State of Israel as if the oranges had never before existed. Trade sanctions and growing production in Spain and Italy meant Jaffa oranges were left abandoned in the port, making their way from ripe to rotting. Orange growers who had fled were no longer considered citizens, no way to return home, left abandoned to make their way across the sea and beg for refuge in someone else’s land.

Slowly the orange orchards disappeared, Jaffa disappeared, annexed behind the bustling “new” city of Tel Aviv. Land that remained was absorbed as property of the State of Israel and the world forgot it had existed before. Trees were removed, roots severed and earth replaced with concrete as canopies shrunk to make way for skyscrapers. The Jaffa orange, the juice of which was once ranked 2nd only to Coca-Cola, was forgotten. There is only one famous orange tree now in Tel Aviv, a floating one, roots trapped in a dirt basket, hanging in the street, suspended, magically disconnected from the land its ancestors once knew. Hung in 1993, long after the world forgot Jaffa.

Oranges are still grown in Palestine. They are still a symbol of strength and love and connection to the beautiful land of home. A connection to history and heritage. In January of this year Yousef Maher Dawas, a young Palestinian writer in Gaza wrote about the destruction of his family’s trees. “But now, three rocket holes plagued my memories. They had left dark grey sand and the scorched remains of trunks and branches from trees that used to bear the fruit of olives, oranges, clementines, loquat, guavas, lemons and pomegranates. I put my hands on my heart to catch it from falling and I felt the three holes there in my heart. This … attack … had successfully destroyed a piece of our past. Our family’s history. Our heritage. ‘But who are we without a past or a history?’, I asked myself.” Yousef was killed, along with the remaining Dawas family, on October the 14th 2023, when an Israeli missile strike hit their home in Beit Lahia, North Gaza.

This article began about Jaffas, but it didn’t really. Jaffas have a long and beautiful history in Aotearoa, but what about the other Jaffa? What was a jaffa before it became a bright red sweet with only vague displaced memories of orange? What about the long and beautiful history in Palestine? What happened to the sweetness?

Written by Lavi Small. She is a chef, a writer and an Eat New Zealand Kaitaki.

Wow that is profound Lavi, Ātaahua 🙏🙏🙏